The Pentagon after the attack on September 11

The Naimisha Journal

Only in Their Dreams by Charles Krauthhammer

Pipedreams and Daydreams by Irfan Husain

The New Wahabi Movement by Sue Lackey

Where Did the Taliban Come From? — A Report

Victory Shifts the Muslim World by Daniel Pipes

Nurturing Young Islamic Hearts and Hates by Rick Bragg

This Is A War That Dare Not Speak Its Name by David Selbourne

India Paying for Its Soft Response to Terrorism by Brahma Chellaney

Are We A Soft State? By Vir Sanghvi

Pakistan's Jihad Factories by Ben Barber

The World View of the Expat Pakistani by Khaled Ahmed

What the Muslim World Is Watching by Foujad Ajami

The Pentagon after the attack on September 11

The following column from the

TIME magazine came to our attention because it was the first article in a major

Western publication to acknowledge hatred of non-Muslims as the foundation of

the ideology that drives Islamic terror. One may summarize it by saying:

"Every bully is at heart a coward." India should take this lesson to

heart. In a religious war, which is what terrorism is, victory must be total. It

is a fight to the finish. You cannot afford to reach a compromise after a

partial victory, as the Hindus did umpteen times, beginning with Prithviraj

Chauhan, last repeated in 1972 after the Bangladesh War.

The author (Krauthammer) recognizes the basic fact of religious

belligerence: the enemy need not have committed any crime; his very existence as

a member of different faith is crime enough for which he deserves to be

exterminated. This is how Pakistan looks at India and also how Islam looks at

Kafirs.

This insight is nothing new, what is new is its open expression in a

major Western publication like TIME. Indian scholars like Sita Ram Goel and Ram

Swarup -- and more recently, V.S. Naipaul -- have been saying the same thing for

years.

Another point: terrorism cannot be treated as a law enforcement problem

where legal defense is accorded to the attacker. It must be treated as war. In

war, we do not worry about the legal rights of the soldier on the opposite side.

We just see him as the enemy to be eliminated. This is how terrorism also needs

to be fought-- not through prosecution and court cases where guilt is

established "beyond a shadow of doubt." After all, a terrorist,

especially a religious warrior, doesn't give us even that chance. We are all

guilty by definition.

Religious war IS terrorism.

The text of Mr. Karauthhammer’s article

The West has not fought a serious religious war in 350 years. America

is too young to have fought any. Our first reaction, therefore, to the

declaration of holy war made upon us on Sept. 11 was to be appalled, impressed

and intimidated. Appalled by the primitivism, impressed by the implacability,

intimidated by the fanaticism.

Intimidation was pervasive during the initial hand-wringing

period. What have we done to inspire such rage? What can we do?

Sure, we can strike back, but will that not just make the enemy even more angry

and determined and fanatical? How can you defeat an enemy who thinks he's on a

mission from God?

How? A hundred days and one war later, we know the answer: B-52s,

for starters.

We were from the beginning a little too impressed. There were endless

warnings that making war on a Muslim nation would succeed only in recruiting

more enraged volunteers for bin Laden, with a flood of fierce mujahedin going to

Afghanistan to confront the infidel. Western experts warned that the

seething "Arab street" would rise up against us.

Look around. The Arab street is deathly quiet. The mobs, exultant on Sept.

11 and baying for American blood, have gone home. There are no recruits

headed to Afghanistan to fight the infidel. The old recruits, battered and

beaten and terrified, are desperately trying to sneak their way out of

Afghanistan.

The reason is simple. We won. Crushingly.

Astonishingly, destroying a regime 7,000 miles away, landlocked

and almost inaccessible, in nine weeks. The logic of victory often eludes the

secular West. We have a hard time figuring out an enemy who speaks in

religious terms. He seems indestructible. Cut him down, and 10 more will rise in

his place. How can you destroy an idea?

This gave rise to the initial soul searching, the

magazine covers plaintively asking WHY DO THEY HATE US? The

feeling that we might be responsible for the hatred directed

against us suggested that we should perhaps seek to assuage and placate. But there is no

assuaging those who see your very existence as a denial of the faith and

an affront to God. There is no placating those who offer you the

choice of conversion or death.

There is only war and victory.

Mullah Omar and bin Laden are animated by a vision. They really do believe

--or perhaps did believe-that their destiny was to unite all the Muslim

lands from the Pyrenees to the Philippines and re-establish the original caliphate

of a millennium ago. Omar took the sacred robe, attributed

to Muhammad and locked away for more than 60 years,

and

triumphantly donned it in public as if to declare his succession to the

Prophet's earthly rule. (Osama harbored similar fantasies about himself, although

he fed Omar's, as a form of flattery and enticement.)

Such visions are not new. Omar's and Osama 's are just as expansive,

just as eschatological, and yet no more crazy than Hitler's dream of the Thousand

-Year Reich or Napoleon's of dominion over all Europe.

The Taliban and al-Qaeda, like Nazi Germany and

revolutionary France, represent not just political parties or power seekers; they

also represent movements. And a movement

carries with it an idea, an ideology, a vision for the future.

That is where the mad dreamers are vulnerable: the

dream can be defeated by reality. [Appeasement

reinforces the dream. Editors.] What was left of Nazi ideology with Hitler

buried in the rubble of Berlin? What was left of Bonapartism with

Napoleon rotting in St. Helena? What was left of Fascism, an idea that

swept Europe and entranced a generation, with Mussolini's body hanging

upside down, strung up by partisans in 1945?

What is left of the great caliphate today? It is a ruin. Caliph Omar is in

hiding; Caliph Osama, on the run.

This is not to say that Islamic fundamentalism is dead. But it has

suffered a grievous blow. Its great appeal was not just its revival of

a glorious past but also the promise that it was the wave of the future,

the inexorable tide that would sweep through not just Arabia but

all Islam--and one day the world. That is why Afghanistan is such a turning

point. It marks the first great reversal of fortune for radical Islam. For

two decades it tasted one victory after another: the Beirut

bombings of 1983 that chased America out of Lebanon; "Black Hawk Down"

that chased America out of Somalia; the first Afghan war that chased the Soviet

Union out of Afghanistan--and led to the collapse of a superpower, no

less. These were heady victories, as were the wounds inflicted with impunity on the

other superpower: the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center, the 1998

destruction of two U.S. embassies in Africa, the 2000 attack on the U .S .S.

Cole. The limp and feckless American reaction to these acts of war

-- a token cruise missile here, a showy indictment there, empty

threats everywhere- only reinforced the radical Islamic conviction that

America was a paper tiger, fat and decadent, leader of a civilization grown

weak and cowardly and ripe for defeat.

For the fundamentalist, success has deep religious

significance. The logic of the holy warrior is this:

My God is great and omnipotent.

I am a warrior for God.

Therefore victory is mine.

What then happens to the syllogism if he is defeated? To understand, we must enter the

mind of primitive fundamentalism. Or, shall we say,

re-enter. Our Western biblical texts speak of a time 3,000 years ago when

victory in battle was seen as the victory not only of one people over another but also of

one god over another. Triumph over the "hosts of Egypt" was of

theological importance: it was living proof of the living God--and the

powerlessness and thus the falsity of the defeated god.

The secular West no longer thinks in those terms. But

radical Islam does. Which is why the Osama tape, reveling

in the success of Sept.11, is such an orgy of religious

triumphalism: so many dead, so much fame, so much joy, so many new

recruits- God is great.

By the same token, with the total collapse of the Taliban,

everything has changed. Omar has lost his robe. The Arab street is

silent. The joy is gone. And recruitment? The Pakistani mullahs who after

Sept. 11 had urged hapless young men to join the Taliban in fighting

America and now have to answer to bereaved parents are facing ostracism and

disgrace. Al-Qaeda agents roaming the madrasahs of Pakistan and the

poorer neighborhoods of the Arab world will have

a much harder sell. The syllogism of invincibility that sustained

Islamic fanaticism is shattered.

We have just witnessed something new in the modern world:

the rollback of Islamic fundamentalism. We have just witnessed the first

overthrow of a radical Islamic regime, indeed, the destruction of radical Islam's home base.

Yesterday the base was Afghanistan. Today it is a few caves and a few hidden cells throughout the world.

Al-Qaeda controls no state, no sovereign territory. It is an outlaw on the

run.

Rollback is, of course, a cold war term. For decades our approach to Islamic

terrorism was like our approach to communism: containment. Do not invade its

territory, but keep it, as Clinton liked to say of Saddam, "in a

box." We tried containing al- Qaeda with a few pinprick

bombings and an attack on a pharmaceutical factory in Sudan. These

were nothing but an evasion, a looking the other way. Sept. 11

proved the folly of that approach. President Bush therefore announced

a radically new doctrine. We would no longer contain. We would attack, advance

and destroy any government harboring terrorists.

Afghanistan is now the signal example. Just as the Reagan

doctrine reversed containment and marked the beginning of the end of the

Soviet empire, the Bush doctrine marks the beginning of the rollback of the

Islamic terror empire.

Of course, the turning of the tide is not the end of the war. This is the invasion of Normandy; we must still enter Berlin. The terrorists still have part of their infrastructure. They still have their sleeper cells. They can still, if they acquire weapons of mass destruction, inflict unimaginable damage and death. Which is why eradicating the other centers of terrorism is so urgent.

We can now, however, carry on with a confidence we did not have before

Afghanistan. Confidence that even religious fanaticism can be

defeated, that despite its bravado, it carries no mandate from heaven. The

psychological effect of our stunning victory in Afghanistan

is already evident. We see the beginning of self-reflection in the

Arab press, asking what Arab jihadists are doing exporting their problems to

places like Afghanistan and the West; wondering why the Arab world

uniquely has not developed a single real democracy; and asking, most fundamentally,

how a great religion like Islam could have harbored a malignant strain

that would rejoice in the death of 3,000 innocents. It is the

kind of questioning that Europeans engaged in after World War

II (asking how Fascism and Nazism could have been bred in the

bosom of European Christianity) but that was sadly lacking in the Islamic world.

Until now.

It is beginning now not because our propaganda is

good. Not because al-Jazeera changed its anti-American tune. Not because a

wave of remorse spontaneously erupted in places like Saudi Arabia.

But because, with our B-52s, our special forces, our smart bombs, our daisy

cutters--our power and our will--we scattered the enemy.

What the secular West fails to understand is that in fighting religious

fanaticism the issue- for the fanatic—is not grievance but ascendancy. What

must be decided is not who is right and wrong- one can never appease

the grievances of the religious fanatic -- but whose God is

greater. After Afghanistan there can be no doubt.

In the land of jihad, the fall of the Taliban and the

flight of al-Qaeda are testimony to the god that failed.

Pipedreams and daydreams

Dawn - Pakistani Daily - Saturday 20 October 2001.

Our paranoid preoccupation with conspiracy theories and the

boundless capacity Muslims have for self-delusion never cease to amaze me. Had

the consequences of these follies not been so tragic, they would have been

downright hilarious.

Consider the horrifying events of September 11 as an example: several weeks

later, millions of Muslims continue to believe that the Israelis were behind the

strikes on New York and Washington. As proof, they assert that 4,000 Jews

absented themselves from their workplaces at the Twin Towers on that fateful

day.

Reasonably educated and intelligent people have declared this rubbish to me as

gospel truth. When I have tried to reason with them, pointing out that there was

no way for anybody to determine the faith of those present or absent from the

WTC buildings within days of the tragedy, there is never a cogent reply. Indeed,

employment records in the United States do not include information about

religion.

My interlocutors simply cannot grasp the reality that Israel would be the last

country on earth to risk the wrath of the United States, the source of so much

of its wealth and power. They argue that Zionists staged this attack to somehow

frame Muslims so that the Americans would become their enemies, but are unable

to explain what Israel would gain by this. Their clinching argument is that

Muslims are simply incapable of planning and carrying out such a complex

operation.

Then there is another school of conspiracy theorists that maintains in all

seriousness that it was actually the American government that attacked its own

cities. The 'reasoning' behind this far-fetched plot is that this would give the

Bush administration an excuse to bomb Afghanistan, throw out the Taliban and

build a gas pipeline across that country from Turkmenistan to the Arabian Sea.

These crackpot theories, ludicrous though they are, are firmly entrenched in the

minds of millions of Muslims. These same people probably also believed the hype

about the invincibility of Iraq's Republican Guards and the 'mother of all

battles' they were supposed to put up against the American-led coalition in the

Gulf War. In the event, they were pulverized by the long bombing campaign that

preceded the land assault, and then mercilessly slaughtered in a 'turkey shoot'

as they fled from their bunkers and trenches.

Now as American planes blast targets across Afghanistan, the Taliban and their

supporters are again falling into the same trap, and boasting that American

troops will 'meet the same fate as the Soviets' when they land. No such thing

will happen because the Americans will simply not send in a large number of

soldiers. Also, the analogy with the Soviet invasion is false as in the latter

case, the Mujahideen had a sanctuary in Pakistan, and the financial and

diplomatic support of a superpower. The Taliban enjoy none of these advantages,

and the firepower the Americans can bring to bear is far superior to the

resources the Soviets could muster.

But we blithely ignore such realities, and are disappointed each time a Muslim

nation is humiliated by a western power. This disillusionment adds to the

bitterness and anger that has built up in the Islamic world towards the West.

But in order to compete more effectively with this perceived foe, many orthodox

Muslims want to turn the clock back: instead of using the modern tools of

reason, logic and science, they seek to return to the imagined purity of early

Islam, purging society of all modern influences so that somehow we would regain

the supremacy and glory of the all-conquering armies that swept out of the

Arabian peninsula fourteen centuries ago.

This romantic daydreaming is fine for a Sunday afternoon after a heavy lunch,

but to base the goals of entire societies on it is madness. Unfortunately, this

shallow rationale is now prevalent in Muslim countries around the globe. Even

educated people have succumbed to this pipedream. In a way, this is a

seductively attractive path: instead of having to put in the hard work involved

in building a modern, progressive society, how much simpler to just transform

ourselves into good Muslims by rigidly following the letter of the holy

scriptures. This will ensure God's blessings on the true believers - blessings

that have been withheld because we have deviated from the path shown to us by

the Almighty.

Unfortunately, as there is no single interpretation of God's revelations and

what constitutes the ideal Islamic society, there has been endless conflict

among the various schools of thought that divide Muslims. Sunnis and Shias are

often at each other's throats; sects are declared 'non-Muslim' for not adhering

strictly to a particular dogma; and for centuries, the slaughter among the

believers has been far bloodier than war with the infidels.

Weakened by internecine conflict and thus easily colonized by Western powers,

most of the Islamic world has been left at the starting blocks in the race for

scientific progress and economic prosperity. Rich Arab states have been unable

to translate their enormous oil wealth into political power or military might;

and when they have, they have mostly used it against their own people or other

Muslims. None of them has sought to use their resources in building up their

educational systems and their scientific base. As a result, they remain

importers of western technology, and send their own children abroad for higher

education.

As Muslims see themselves falling further and further behind, and watch

impotently as Palestinians and Iraqis are killed and humiliated, their rage

against their own rulers and the United States mounts steadily. In a relatively

new development, young Muslims born, raised and educated in the West are being

radicalized into taking up arms for Muslim causes. And as the United States is

perceived as the source of so much angst and suffering in the Muslim world,

there is every possibility that these home-grown young militants will launch the

next wave of attacks.

In this low-intensity war without end, there will be no victors and no losers,

only hostages to hatred and suspicion on both sides. Unfortunately, there is no

indication that either side will change policies and attitudes any time soon.

Among fundamentalist Muslims, rationality and a scientific approach are anathema

as they would be marginalized and dogma would be questioned in a modern

dispensation. But until Islam has its own Reformation, Muslims will continue to

wallow in the past while ostrich-like, they keep their heads firmly in the sand.

|

The 'New Wahabi' movement By Sue Lackey, MSNBC

|

||

| Increasingly, Saudi-funded sect viewed as central to U.S. war on terrorism |  |

|

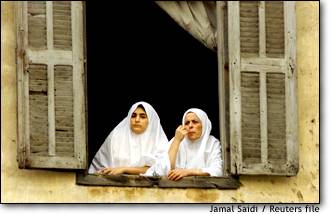

| Sunni

Muslims watch as anti-American demonstrators chant slogans supporting

Osama bin Laden in the Lebanese town of Tripoli last Friday. |

||

|

BEIRUT, Lebanon, Oct. 17 — In a middle-class neighborhood in West Beirut near the squalor of the Shatila refugee camp, Palestinians live side by side with Shiite Muslims who fled the Israeli occupation in southern Lebanon. Graffiti and banners reflect the local sympathy for the “martyrs” of their respective causes: the fight for a Palestinian homeland and the Shiite Hezbollah movement, considered a terrorist group by the U.S. government. Nestled among these militant groups, however, are religious schools that U.S. intelligence officials regard as far more dangerous. They are the madrassas of the Saudi-funded Wahhabi sect, part of a worldwide network of Muslim extremists that now figures at the center of the Sept. 11 attacks. |

|

IN

THIS NEIGHBORHOOD and several others like it, puritanical Wahhabi schools

indoctrinate young men in radical militancy. Between the ages of 7 and 15,

they are taught the fundamentals of strict Islam and religious

obligations. Between the ages of 15 and 25, these young men are trained to

fight and prepared for the jihad, or holy war — in this case conquest of

Wahhabi Islam. The students they are charged with fulfilling missions

related to the jihad. |

|

|

LARGE NETWORK

It is important to stress that not all of the young men who attend

Wahhabi schools will turn to violence. A number will go on to become

religion teachers themselves. |

|

| DOUBLE-DEALING

Over

the past 10 years, Saudi Arabia, either directly or indirectly through

non-governmental organizations, has financed all of the Wahhabi movements

in the region, says one prominent Islamic scholar in Lebanon.

|

|

Since then, other clerics inside and

outside the country have added their voices, in effect ex-communicating

Saudi Arabia’s ruling family for aiding the U.S.-led attacks on

Afghanistan, which is ruled by the Taliban and has been a refuge for bin

Laden.

Since then, other clerics inside and

outside the country have added their voices, in effect ex-communicating

Saudi Arabia’s ruling family for aiding the U.S.-led attacks on

Afghanistan, which is ruled by the Taliban and has been a refuge for bin

Laden.For their part, the United States and Britain, which saved the Saudi kingdom from almost certain conquest by Iraq in 1990-91, are furious at the emerging evidence that Saudi money bankrolled the killers of 6,000 or more Americans on Sept. 11. A

NEW INTERPRETATION |

|

Now, bin Laden has remade the Wahhabi movement in his own image. First and foremost, bin Laden would like to see New Wahhabism overthrow the Saudi government, which he denounces for corruption and for allowing U.S. soldiers to be based on Saudi soil following the Persian Gulf War. NO DEVIATION The West and Arab governments such as Saudi Arabia’s are not the only targets of the New Wahhabism. This harsh fundamentalist view of Islam sees all who do not adhere to its beliefs as infidels, even moderate Sunni Muslims and Shiites, who form the majority in Iran and Lebanon and substantial minorities in other Arab countries. Also beyond the pale to these puritans, of course, are members of any other religion. Many Islamic scholars who disagree with these views see bin Laden’s call for a holy war against America as a distraction from his larger intentions. In reality, they say, the Wahhabis’ personal and organizational beliefs ultimately will force a war within Islam, as well. “There is hatred between Wahhabism and Shiaism,” says an Arab expert on fundamentalism. “This is very crucial. They consider that everyone has deviated.” The repressive nature of many Arab regimes has provided fertile ground for this ideology, particularly among poorer and less educated people who have no access to the window that the Internet or satellite television provides to the outside world. Where many governments have been unable or unwilling to provide social services, Islamic associations, including Wahhabi groups, have stepped in, fostering loyalty to Islam instead of a state. To keep social unrest at bay, many regimes, from Egypt to Saudi Arabia to Pakistan, encourage demonization of Israel and the West. WHO WILL WIN? Fundamentalism, with its abhorrence of modernity, ensures that the poor and illiterate will receive one narrow view of world events. “Bin Laden has recruited without a physical presence in the street,” says one Arab expert on fundamentalism. “Why? Because whether you like it or not, the average citizen in this part of the world is perceiving what’s happening as a clash of civilizations, despite the emphasis of the United States and Europe.” The United States may destroy the Taliban with its airstrikes, but this expert says that the Wahhabis will win out in the end because they are disciplined and have the money and recruiting system to build their following. “The [other Islamic factions] fight the Wahhabis as an independent movement, they think they are backwards. But finally they are going to give up and become Wahhabis. The money is coming from the Wahhabis; it’s as simple as that.”

|

Victory Shifts the Muslim World

by Daniel Pipes

New York Post

November 19, 2001

http://www.nypost.com/postopinion/opedcolumnists/34628.htm

Early on Nov. 9, the Taliban regime ruled almost 95 percent of Afghanistan. Ten days later, it controlled just 15 percent of the country. Key to this quick disintegration was the fact that, awed by American air power, many Taliban soldiers switched sides to the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance.

According to one analyst, "Defections, even in mid-battle, are proving key to the rapid collapse across Afghanistan of the formerly ruling Taliban militia."

This development fits into a larger pattern; thanks to American muscle, Afghans now look at militant Islam as a losing proposition. Nor are they alone; Muslims around the world sense the same shift.

If militant Islam achieved its greatest victory ever on Sept. 11, by Nov. 9 (when the Taliban lost their first major city) the demise of this murderous movement may have begun.

"Pakistani holy warriors are deserting Taliban ranks and streaming home in large numbers," reported The Associated Press on Friday. In the streets of Peshawar, we learn, "portraits of Osama bin Laden go unsold. Here where it counts, just across the Khyber Pass from the heartland of Afghanistan, the Taliban mystique is waning."

Just a few weeks ago, large crowds of militant Islamic men filled Peshawar's narrow streets, especially on Fridays, listening to vitriolic attacks on the United States and Israel, burning effigies of President Bush, and perhaps clashing with the riot police. This last Friday, however, things went very differently in Peshawar.

Much smaller and quieter crowds heard more sober speeches. No effigy was set on fire and one observer described the few policemen as looking like "a bunch of old friends on an afternoon stroll."

The Arabic-speaking countries show a similar trend. Martin Indyk, former U.S. ambassador to Israel, notes that in the first week after the U.S. airstrikes began on Oct. 7, nine anti-American demonstrations took place. The second week saw three of them, the third week one, the fourth week, two. "Then - nothing," observes Indyk. "The Arab street is quiet."

And so too in the further reaches of the Muslim world - Indonesia, India, Nigeria - where the supercharged protests of September are distant memories.

American military success has also encouraged the authorities to crack down. In China, the government prohibited the selling of badges celebrating Osama bin Laden ("I am bin Laden. Who should I fear?") only after the U.S. victories began.

Similarly, the effective ruler of Saudi Arabia admonished religious leaders to be careful and responsible in their statements ("weigh each word before saying it") after he saw that Washington meant business. Likewise, the Egyptian government has moved more aggressively against its militant Islamic elements.

This change in mood results from the change in American behavior.

For two decades - since Ayatollah Khomeini reached power in Iran in 1979 spouting "Death to America" - U.S. embassies, planes, ships, and barracks have been assaulted, leading to hundreds of American deaths. In the face of this, Washington hardly responded.

And, as Muslims watched militant Islam inflict one defeat after another on the far more powerful United States, they increasingly concluded that America, for all its resources, was tired and soft. They watched with awe as the audacity of militant Islam increased, culminating with Osama bin Laden's declaration of jihad against the entire Western world and the Taliban leader calling for nothing less than the "extinction of America."

The Sept. 11 attacks were expected to take a major step toward extinguishing America by demoralizing the population and leading to civil unrest, perhaps starting a sequence of events that would lead to the U.S. government's collapse.

Instead, the more than 4,000 deaths served as a rousing call to arms. Just two months later, the deployment of U.S. might has reduced the prospects of militant Islam.

The pattern is clear: So long as Americans submitted passively to murderous attacks by militant Islam, this movement gained support among Muslims. When Americans finally fought militant Islam, its appeal quickly diminished.

Victory on the battlefield, in other words, has not only the obvious advantage of protecting the United States but also the important side-effect of lancing the anti-American boil that spawned those attacks in the first place.

The implication is clear: There is no substitute for victory. The U.S. government must continue the war on terror by weakening militant Islam everywhere it exists, from Afghanistan to Atlanta.

PESHAWAR, Pakistan, Oct. 13 — A thousand years ago, in the days of the camel caravans, storytellers gathered here in the tea shops and brought the outside world and all its thoughts and ideas to the bazaar. As the vendors hawked silk, spice and rich tapestries and traders herded beasts through streets thick with smoke from cooking fires, travelers from distant lands and differing religions told stories about moguls, magic, wit and wisdom. In time, the bazaar came to be known as Qissa Khwani — the Bazaar of the Storytellers.

Now, the streets are still choked with donkey carts, and meat still sizzles on open pits, but the vendors are poor men selling simple things. Blaring car horns drown out all other sound, just as the teachers and students in the Islamic seminaries that surround this bazaar have drowned out all conflicting ideas, all unacceptable thoughts.

The storytellers no longer come. There is just one story now, at least one acceptable story. It is the one taught in the seminaries, called madrassas, that have become incubators in Pakistan for the holy warriors who say they will die to defend Islam and their hero, Osama bin Laden, from the infidels. In many of the 7,500 madrassas in Pakistan, inside a student body of 750,000 to a million, students learn to recite and obey Islamic law, and to distrust and even hate the United States.

"Jihad," shouted a little boy, from a high window in a madrassa just steps from the Khwani Bazaar. He grinned and waved as foreign journalists snapped his photograph, but, on the streets below, older students had massed for demonstrations that would end in clouds of tear gas and smoke from burning tires, as young men jumped through fire to prove their faith and ferocity.

President Bush and diplomats from the West have taken great pains to point out that the war on Mr. bin Laden and the Taliban of Afghanistan is not a war on Islam, but in many madrassas here in Pakistan — especially those near the border with Afghanistan — militant Muslims lecture students that the United States is a nation of Christians and Jews who are not after a single terrorist or government but are bent on the worldwide annihilation of Islam.

The madrassas' sword is in the narrow education they offer, and the devotion they engender from students from the poorest classes who, without them, would have nowhere to go, or go hungry.

At the Markaz Uloom Islamia madrassa in Peshawar, Muhammad Sabir, 22, motioned to the eerily quiet compound, devoid of students. Final exams are over, he said. The scholars, many of them, have left to fight against the United States. "They have gone for jihad," said Mr. Sabir, a student there. "It is our moral and religious duty." He said the words automatically, woodenly, as if repeating his elder's recitation of the Koran.

"There is no practical training of terrorists here," said Asif Qureishi, an Islamic scholar and the son of Maulana Mohd Yousaf Qureishi, who heads the Darul-Uloom Ashrafia madrassa in Peshawar. There are no weapons, no knives or guns, no weapons training. The madrassas hone only the mind, he said.

"We prepare them for the jihad, mentally," said Mr. Qureishi, whose duties at the madrassa include the call to prayers. In a small room at the madrassa, students nodded appreciatively at his words. Some were no more than 10.

"The minds are fresh," he said. In his tiny office, a bag of rice rests against a wall. Outside the door, a student hefts the carcass of a slaughtered goat.

What the students hear, in compounds that range from spartan to squalid, is a drumbeat of American injustice, cruelty and closed-mindedness — the United States is just that way, the elders say.

"They send cruise missiles against gravestones," said Al-Sheikh Rahat Gul, the stick-thin, 81-year-old maulana who heads Markaz Uloom Islamia in Peshawar, a madrassa with about 250 students.

The Americans kill only innocents, said the maulana, a large pair of thick-lensed, black-framed glassed sitting crookedly on his head. "The Koran forbids the killing of females, children, elders and cattle," he said. "That is war. That is not holy war." Sons of Islam must answer that tyranny with holy war, he said.

He condemns the World Trade Center attack but dismisses any connection to this part of the world. "The Jews have done this," he said, calling the attacks a plot by Israel to draw the world into war. "And the Hindus are just like them." It is repeated madrassa by madrassa, the company line of the militants and the poorer classes from which they come, spreading out from the student body to the shops and foot traffic.

Maulana Gul proudly points to a cartoon on the back of a pamphlet at his madrassa that shows Afghanistan encircled by a chain, and the chain is secured by a padlock that is labeled "United Nations." Inside the chain are weeping children. Hands reach from all directions with offerings of food, money and grain, hands are grabbed at the wrist by other hands labeled "U.S.A.," preventing that aid from getting to the starving people.

In the madrassas, students ranging in age from 7 or 8 to men over 20 are taught a strict interpretation of the Koran, including the duty of all Muslims to rise up in jihad. There are no televisions and some madrassas do not even allow transistor radios. There are no magazines or newspapers except those deemed acceptable by the elders. The outside world is closed to them, and many of the students seem puzzled when asked if they mind that. Their teachers, most of them respected elders, tell them what they need to know, the students said.

Almost all the leadership of the Taliban, including Mullah Muhammad Omar, was educated in madrassas in Pakistan — most of them in a single madrassa, Jamia Darul Uloom Haqqania in Akora Khatak in the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan. The anti-American protests that have filled the streets in Islamabad, Peshawar, Quetta and Karachi have been planned in madrassas — their maulanas, the elders who run the schools, are the spiritual hub of the protests.

In Quetta, after the United States began its missile attacks on the Taliban, 300 Afghans who had attended madrassas in Pakistan crossed the border to join the jihad. Every day, said madrassa students, Pakistanis slip over the border to join them.

The Times, SATURDAY

NOVEMBER 17 2001

To American and British politicians, the week’s events in Afghanistan have been triumphs. To the Northern Alliance warlords, and the Pakistanis, they have been another chapter in the history of their region’s inter-tribal, and inter-Muslim, conflicts that is being written. But the impoverished statements of our leaders since September 11 reveal that historical knowledge plays no significant role in their thinking, despite the perilous venture upon which they are engaged.

In consequence, we are

being led to battle by those who give every sign of not being sufficiently aware

of what they are doing, and who are not, therefore, fit to be our guides.

Tomahawks in hand, they

have promised us that “terrorism” will have “nowhere to hide”. But we

are not engaged in a war against terror. It is a war provoked by Islamism,

directed against it, yet which dare not tell its name, and in which there cannot

be the “victory” the politicians promise. The Northern Alliance carries the

Koran in its knapsacks, too.

The outrages against the

US were seen as bolts from the blue, but are different only in degree from

earlier Islamist attacks. Yet there had already been millions of lives lost in

the Islamic world’s past decades of war. At least since 1947, the year in

which Arnold Toynbee warned of the “sleeping giant”, or since 1952, when the

Egyptian revolution brought Nasser to power, Islam, waking from three centuries

of torpor, has been astir with internecine struggle and assertion against the

West. Since then its internal and external conflicts have raged, drawing in

Islamic and non-Islamic nations alike.

Iran and Iraq have fought

an eight-year war; Syria has occupied much of Lebanon; Iraq has sought to ravage

Kuwait. Sudanese, Egyptian, Nigerian, Pakistani and other Islamists have been

killing Christians; Egyptians and Algerians have each battled to protect

themselves against fellow Muslims; the Chinese, Indians, Russians and now

Americans have faced local Islamic attack. Today, the cry of jihad against the kuffar,

or infidel, is on the lips or in the hearts of young Muslims the world over,

while Western relativists consider how “pluralism” can be reconciled with

the aims of those who would see our very societies fall.

Postwar and post-colonial

Islamism, revived and still to revive much further, has expressed itself in

different ways. It has taken political form in Arab nationalism, as in the

seizure of the Suez Canal in 1956; economic form, as in the use of the oil

weapon against the West in 1973; religious form, as in the Iranian-inspired

arousal of worldwide Islamic fervour. In such context a bin Laden, important as

he is, is not of greater historical significance than a Nasser or an Ayatollah

Khomeini.

All of them, including the

suicide bomber, are apostles of the Islamic resurgence, as historians of

Islam’s modes of warfare (and conquest) know. In these past decades, a cat’s

cradle of links has been woven across the Islamic world. Ahmed Shah Massood, the

Taleban’s then leading opponent, was assassinated in September by Algerians

with Belgian passports and with visas to enter Pakistan issued in London.

Armouries have been

amassed by the more dangerous Islamic states with the help of the historically

unseeing West. Such filiations and weapons are the instruments of no abstract

“terror” or “unreason” but of an insurgency of faith, cruelty, pride and

anger that in intention would master the globe. Even if bin Laden were killed

tomorrow, or Israel disappear from the face of the earth, this insurgency would

continue.

It has occurred at a time

when the West’s knowledge of Islam, and even of its own history, has never

been less. The only truly historical question asked in America since September

11 has been the vacuous “Why are we so hated?” It is a question, which the

Americans have been unable to answer. Muslims with a long memory have no such

problem.

In the light of its

battles with medieval Christianity and with varieties of modern imposition,

Islam’s “anti-Americanism”, “anti-Westernism” and “anti-Zionism”

are as we ought to have expected. In the First World War, the Ottoman Empire

readily joined the Axis powers; in the Second, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem was

Hitler’s de facto gauleiter in the region. No one in their (historical) senses

should be surprised that today’s Palestinian Islamists would uproot Israel, a

nation conceived with the West’s support as the Ottoman Empire disintegrated.

Turn back the pages of the

record and the century-old voices of premonition, including those of Jews, about

Israel’s uncertain fate as an “island in an Arab sea” can already be

heard. “Most Jews are no longer Oriental,” the early Zionist Theodor Herzl

confided to his diary; a “transplantation” to Palestine would be

“difficult to carry out”.

Israelis have always had a

fight on their hands. Yet knowing so is to be better armed than are Americans

— for all their firepower — as they try to square up to foes whom they

cannot name, and of whose faith and past they know too little. Clio, the goddess

of history, is not likely for this reason to be on the side of the West, which

is more blind than it can afford to be or than its peoples deserve, while

Muslims now walk with a spring in their strides. They have good reason to do so,

even as the Taleban falls. For the sharp end of a resurgent Islam is a more

powerful and long-term adversary of the Western democracies than was Nazism.

When I was in the US in

September, I offered the New York Times Magazine an account of the

post-1945 decades of Islam’s upheavals. One of its editors told me it was

“interesting, but we don’t do history”. But if the Americans (and British)

“don’t do history”, history will do for us.

David Selbourne is the author of The Spirit of the Age and The Principle of Duty

THE HINDUSTAN TIMES, DECEMBER 14, 2001

INDIA PAYING FOR ITS SOFT RESPONSE TO TERROR

Brahma Chellaney

The terrorist assault on the symbol of Indian democracy at a time when jehadis

are on the run elsewhere in the world reflects the widely perceived softness of

the Indian state and the costs it is paying for its compromises with the forces

of terrorism.

India's talk-tough-but-act-meek approach has emboldened transnational

terrorists, who pick their targets carefully to get maximum propaganda value and

show that they can strike anywhere, anytime. Earlier, they struck at the Red

Fort, which symbolises Indian authority, as India has been ruled since the 17th

century by those who occupy it.

When the terrorists attacked the Jammu and Kashmir legislature, Vajpayee wrote

to President Bush that India's patience was wearing thin. Now that the Indian

Parliament has been attacked, citizens are awaiting the answer whether, in

Vajpayee's view, the government's patience has run out or there is still room

for forbearance.

Vajpayee needs to think over why fidayeen attacks have occurred only under his

prime ministership and why even today, when jehadis look such a beaten lot

elsewhere, major acts of terrorism continue to occur in Kashmir and New Delhi.

Empty brave words against terrorism mean nothing. India has to fight its own war

on terrorism and not expect that the United States will fight for it.

Successive Indian governments have treated terrorism essentially as a law and

order issue. To treat terrorism as a law and order problem is to do what the

terrorists want - sap your strength - and bring the republic under a

self-imposed siege. No amount of security can stop terrorism if the nation is

reluctant to go after terrorist cells and networks and those that harbour,

encourage or fund terrorists.

Western policy-makers should be concerned over the Parliament attack because

India is a sort of laboratory where major acts of terror are first tried out

before being replicated in the West. The logic is that if India, the world's

largest democracy, can be shaken, so can other democracies.

For example, the 1988 Pan Am 103 bombing replicated the midair bombing over the

Atlantic of an Air-India flight from Canada in 1985. Similarly, the 1993 World

Trade Centre attack was modelled on the bombings weeks earlier that killed many

inside high-rise buildings in Mumbai in a terror campaign designed to disrupt

India's financial market. Parallels also have emerged between the 1999 hijacking

to Kandahar of Indian Airlines flight IC-814 and the September 11 suicide

hijackings, including the similar use of box-cutters and the terrorists'

knowledge of cockpit systems.

If any state strikes deals with terrorists, it not only encourages stepped-up

terrorism against its own interests but also creates problems for other nations.

A classic case is India's ignominious surrender to the hijackers of flight

IC-814. One freed terrorist hand-delivered by the foreign minister is the

suspected financier of Mohammed Atta, the alleged ringleader in the September 11

terrorist strikes. Another released terrorist founded a group in Pakistan that

has claimed responsibility for major Kashmir strikes.

Exactly a decade before this surrender, India spurred the rise of bloody

terrorist violence in Kashmir by capitulating to the demands of abductors of the

then home minister's daughter, Rubaiya Sayeed. Under Vajpayee, India has held

secret negotiations with terrorist groups, including the Hizbul Mujahideen and

the ISI-funded Hurriyat Conference. Terrorists see India as a soft target

because it imposes no costs on them and their sponsors.

Terrorism has to be fought with a prudent, comprehensive strategy that employs

diplomatic, economic, political, military, and legal instruments. But the only

instrument India has sought to employ since the 1980s is a domestic

anti-terrorism law, which cannot yield results by itself. Can anybody who looks

at the bloated size of the Pakistan High Commission in New Delhi get the

impression that India treats Pakistan as the sponsor of cross-border terrorism?

THE HINDUSTAN TIMES, DECEMBER 23, 2001

ARE WE A SOFT STATE?

Vir Sanghvi

Just before the Agra summit, the Foreign Secretary hosted a small lunch for

editors and columnists in her South Block office. The idea, presumably, was for

the mandarins of the Foreign Office to tell us what to expect in Agra. But

because Chokila Iyer is such a gracious, well-mannered hostess, the mandarins

never really got a chance to say very much at all.

Instead, the journos hijacked the lunch and told the diplomats how to do their

job. (Do not be surprised. This happens all the time). For the most part, this

consisted of familiar peacenik advice — it is up to us to make Agra a success,

to give poor dear General Musharraf something he can take back to his people

etc. — so the foreign office mandarins, who had a more realistic assessment of

what to expect, switched off.

During a brief lull in the lectures from the lunching journos, our High

Commissioner in Islamabad, Vijay Nambiar, did manage to get a word in edgewise.

It proved to be the most perceptive thing that anybody said at the lunch.

The big revelation for him during his stint in Pakistan, he said, was that

Pakistanis and Indians had very different attitudes. For the Pakistanis, truth

was simple and one dimensional. For Indians, truth was a complex commodity. We

always accepted that there were many points of view and many dimensions to the

truth. Pakistanis, on the other hand, regarded the truth

pretty much as what they wanted it to be.

The consequence, he suggested, was that the Pakistani position always came

across as straight-forward and forthright. But ours came across as too complex

for simple arguments.

I have thought a lot about Vijay’s distinction over the last week. Every

newspaper and every TV channel has been considering India’s response to the

attack on Parliament. There have been notable exceptions (chiefly Brahma

Chellaney whose piece in the HT five days ago appears to have become the basis

of government policy) but most Indian journos have spent their time hemming and

hawing.

Yes, of course, terrorism is bad, they say. But you know, we need to understand

Musharraf’s compulsions. Perhaps we should give him another chance. Or: Bush

is really on our side, you know, but he’s got this Afghan operation going so

we need to understand his compulsions. Or: the international community is united

in the war against terrorism but, you know, we are both nuclear powers. So

naturally they will be concerned and we need to understand those compulsions.

Curiously, nobody talks about the need to understand

India’s compulsions.

Contrast this it-is-a-complex-issue-and-we-need-to-consider-everything approach

with the Pakistani position on the Parliament attack. It is as straight-forward

as ours is complex.

Basically, all the Pakistanis are saying is this: we didn’t do it and let’s

see if you can prove otherwise.

As usual, it is the Pakistani position that is more effective. Of course we

can’t provide proof of the kind that will satisfy Pakistan. Even when the

terrorists themselves go on TV and say that they were backed by Pakistan, these

confessions are dismissed by the Pakistanis as being secured through torture.

The point is that nobody can ever provide strong legal proof of the kind that

the Pakistanis are demanding. Even the Americans, who have now taken up the

share-the-evidence-with-Pakistan position, had no proof at all of Osama bin

Laden’s involvement when they began bombing Afghanistan. They didn’t even

have the kind of confessions that we have now secured. But they launched their

attack anyway — and Pakistan supported them.

The understand-everybody’s-compulsions-except-our-own

position embraced by the Indian intelligentsia demonstrates a fundamental

weakness in our view of the world, at least in relation to terrorism.

Two examples will show what I mean.

In December 1999, when the hijackers took IC 814 to Kandahar, it should have

been staggeringly obvious to everybody that the Taliban were hand in glove with

the terrorists. To be fair to our security services, they reported as much to

their political masters and pointed out that no commando rescue mission was

possible because the Taliban had placed stinger missiles on the runway to blow

up any Indian plane that attempted to land such commandos.

Despite all this, our Foreign Minister decided to go to Kandahar to take custody

of the hostages. He was humiliated even before he got off the plane. Maulana

Masood Azhar, the terrorist we released in return for the passengers, was the

first to alight and the Taliban received him with hugs and kisses. By the time

Jaswant Singh descended from the aircraft, the Taliban reception party had

departed, taking Azhar away in a huge carcade. Jaswant was left to cool his

heels on the tarmac for a quarter of an hour.

No matter. He still managed to hold hands with the Taliban Foreign Minister for

the TV cameras and paid fulsome tributes to the Afghan government for its

‘help’ during the hijacking. Those pictures — of Jaswant and the Taliban

hugging each other — will haunt the Vajpayee government forever.

Why did he do it? Well, he thought that once he was there, he should be nice to

his hosts. And why was he there in the first place? Ah, well, that’s a complex

question to which there is no simple answer.

A second example. Shortly after the September 11 attacks, it was clear that the

Americans would have to retaliate. It was as clear that they would ask the

countries of South Asia for help. The sensible thing to have done would have

been to express sympathy for those who lost their lives in the attacks

(including hundreds of Indians) and to have waited for the American request.

Instead, Jaswant Singh (yes, him again) shot his mouth off and told the press

that India was ready to offer operational assistance — even before it had been

requested. Of course, the Americans didn’t need our assistance. But in their

minds, we became the kind of country they could take for granted.

Contrast our over-eager foolishness with the shrewdness of General Musharraf’s

response. He expressed sympathy but offered nothing. Instead, he engineered

anti-American and pro-Taliban demonstrations. When the American request came, he

said that he would like to help but the public mood was against it. At this, the

Americans offered him billions of dollars and began an extensive courtship that

persists to this day.

You don’t need to be a genius to work out which approach has yielded the

better result. We understood America’s compulsions and eagerly offered

assistance. Our reward is to be isolated in our fight against terrorism.

Musharraf made America understand Pakistan’s compulsions. His reward is to be

America’s new pin-up boy.

I mention these two examples because it seems to me that we are in danger of

making a third mistake. Instead of concentrating on what steps we will take to

stop the menace of cross-border terrorism, our intelligentsia is busy finding

reasons to do nothing. Understand Bush’s position, they say. Give poor Pervez

another chance. Let the world community finish with Afghanistan, then maybe

they’ll have time for us.

Contrast this it-is-a-complex-situation response to the position taken by the

American intelligentsia after September 11. Did the US media say “we should

wait till we get proof against bin Laden”? Did intellectuals say, “if we

attack Afghanistan, we will turn the world’s Muslims against us”? Did the

intelligentsia warn, “wait a while because if we attack now, we may

destabilise Musharraf”?

Of course, they did not.

It was not as though the Americans were blind to these considerations. They knew

they were short of proof, they knew they risked alienating Muslims and

destabilising Pakistan. But they also knew that these were risks worth taking.

When a country is attacked by foreign terrorists, it must first fight back and

defend itself. Everything else is secondary.

Our problem is that Pakistan — and perhaps the rest of the world — sees us

as a soft state. We give the impression of having a mouth of steel and a fist of

plasticine. We will not consider any compromise on Kashmir, but we will not go

to war to defend it. We say we will fight all terrorism but Jaswant Singh will

fly to Kandahar to cuddle the Taliban. We will condemn cross-border terrorism

but we will not cross the border to fight it.

If we are to act firmly against the terrorist menace then we must abandon our

humming and hawing. We must stop thinking about other people’s compulsions and

worry about our own. If we believe that Pakistan is behind the terrorists, then

we must treat it as the enemy. We must forget about confidence building

measures, about poor Pervez’s problems and about candles on the Wagah border.

It is not my case that we should necessarily go to war. All war is bad and

should be avoided as much as possible. But it is also true that if you rule out

war even before you begin taking any kind of action, then nobody will take you

seriously. For your protests to make any difference, your enemy must know that

you are both willing and able to fight.

On Friday, our government was so angered by President Bush’s clean chit to

General Musharraf that it recalled our High Commissioner from Pakistan. It only

took a few hours for the message to hit home. By that same evening, Washington

had changed its stance and asked Musharraf to take action against terrorists

operating from Pakistan.

The way ahead is to keep up that kind of pressure. The lesson of the US’s

Afghan operation is that finally, you don’t need summits and you don’t need

bus rides. If you are to fight terrorists, then the only things that work are

courage, might and determination.

It is time for India to show that we will not be pushed around any longer.

(Editors' comment: Mr. Vir Sanghvi, who wrote this article was himself the kind of 'intellectual' that he is condemning now. At the heart of the problem is the education system, especially in the humanities, that produces an elite that still carries a colonial mindset-- that the first duty of an Indian is to please others.)

PAKISTAN'S JIHAD FACTORIES

Ben Barber

Afghanistan's Taliban studied in the madrasahs-the Islamist religious

schools-of Pakistan, where some 1.75 million students are currently preparing

to fight for Islam around the world.

It was hard to imagine that the smiling children playing a quick game of

cricket on a rooftop courtyard in the heart of Pakistan's ancient cultural

capital of Lahore were learning to be killers.

The head of their madrasah (religious school), a portly man with a white

turban and white Pakistani clothing, had invited me to see for myself how his

students were treated and what they had learned. So I'd climbed some steps in

the Khuddamuddin madrasah, one of perhaps 7,000 such religious schools in

Pakistan, and found the boys at play, taking a break from classes.

In a few moments chatting with them, I quickly learned that their major topic

of study was jihad, or holy war. The nearly 2,000 students expect to fight

infidels in Chechnya, Afghanistan, Palestine, or Indian Kashmir once they

complete their studies at the madrasah, located inside the walls of the old

city of Lahore.

This school and others like it have prospered in recent years, in part because

of the failure of the state-run educational system. In Pakistan, the

illiteracy rate among adults is estimated at 70 percent.

About 1.75 million students are enrolled in the schools, though it is not

clear how many of the academies are devoted to preparing their students for

jihad. Some may focus only on religious studies. It is certain, however, that

each time the repressive Islamic Taliban regime in Afghanistan needs to mount

a spring offensive against its rebel opponents, tens of thousands of students

from Pakistani madrasahs pour over the border in trucks to join the jihad,

according to reports in the Jane's defense publications. Thus, the system of

madrasahs has become a hatchery for tens of thousands of Islamic militants who

have spread conflict around the world. Incidents in the Philippines,

Indonesia, Russia, Central Asia, and at New York's World Trade Center have all

been linked to graduates of the madrasahs. Indeed, Pakistan is terrorism's

fertile garden.

Khuddamuddin is run by Mohammed Ajmal Qadri, leader of one of the three

branches of the fundamentalist Jamiat Ulema Islam party, who told me that

nearly 13,000 trained jihad fighters have passed through his school. At least

2,000 of them were in or on their way to Indian-held Kashmir.

Converting the World to Islam

Qadri, polite and well spoken in the British-accented English of South Asia,

offered an American guest tea and then calmly disclosed that the modern

concepts of tolerance and cultural understanding have not made inroads into

his thinking.

"Eventually,

all people must become Muslim, including the Christians and Jews of the United

States," he said in an interview. "The world has to go the way we

want. It's our divine right to lead humanity." He apologized for a lack

of time to spend with a visitor, saying he was preparing for yet another of

his frequent visits to the United States. There, he preaches in the hundreds

of new mosques built in the last decade by Muslim immigrants and raises money

for his school--where he teaches his children to kill those who stand in the

path of Islamic dominance in the world.

Up on the stone rooftop courtyard of his 110-year-old school, the students

were taking advantage of a free period to hit a cricket ball, run, and wrestle

like children anywhere in the world. But one slightly built boy explained how

he and his classmates were being directed toward a life of violent struggle.

"Most kids here go for jihad, and I will too, God willing," said

14-year-old Obeidulla Anwer, speaking in Urdu through a translator.

"Jihad is to fight for Islam and the pride of Islam."

Mullah Omar

Like most of his classmates, he will leave the school at about age 18 and

go to a military training camp in Pakistani-controlled Kashmir, Afghanistan,

or some other secret location. After that training, he said, "We go to

fight in Kashmir, Chechnya, Palestine, Afghanistan."

Asked whether he was prepared to hurt or kill, the delicate, dark boy said:

"I will hurt those who are enemies of Islam. And I know that I could be

hurt or killed."

The chances that Obeidulla will die violently are high. A 23-year-old fighter

with another Islamic militant group, Hizbul Mujahideen, said that five of the

eight young men in his squad had died during his 18 months of fighting against

Indian troops in Kashmir, where an estimated 30,000 people have died in civil

strife since 1989.

Obeidulla was asked how he would recognize the enemies of Islam. "If I

greet them with 'Salam Aleikum' and they won't say it back," he answered.

The boy was asked: "Since most Americans do not know Arabic and cannot

know how to respond to the traditional Muslim greeting, are they enemies of

Islam?" The boy looked confused. "I don't know," he said,

looking expectantly at his hovering teachers, who also appeared confused by

the question. Asked directly whether all non-Muslims were anti-Muslim, he did

not need to check with his teachers. "No," he said firmly.

The school is preparing Obeidulla and his classmates for the hard life of

soldiers with an experience that provides little comfort or privacy. The

children all sleep on the floor of the school's mosque in sleeping bags, which

they roll up each morning. They rise at 3:00 a.m. for study and prayers with a

break for play around 4:30 a.m. At 7:30, they have breakfast and then study

until 11:00, when they sleep for two hours. They pray, study, have lunch,

pray, study, and pray again until dinner at 9:30 p.m., after which they go to

the mosque to sleep. They have no room or even a bed of their own.

Why the Madrasahs Thrive

Parents choose this hard life for their children for a variety of reasons,

with religious conviction and the poverty of village life both playing major

roles.

Religion dominates life in Pakistan, where the national airline begins its

flights with a reading from the Qur'an or a prayer. Politicians, even those

educated in London or Boston and living apparently Westernized lives, vie in

calling for stricter Islamic laws.

Poverty is the other goad. A half-hour drive from Lahore and just a stone's

throw from the Indian border crossing at Wagha, farmer Mohammed Shaffi

explained why his 13-year-old son attends the local madrasah and not a public

school. In the madrasah--many are funded by donations from Saudi Arabia and

other Muslim nations or groups in wealthy countries--he memorizes the Qur'an

in Arabic, which he cannot understand. But he is not being taught to read and

write the national language, Urdu.

"How can a poor man educate his son?" asked Shaffi, leaning for a

moment over the mud wall he was building around his tiny rice paddy in the

village of Dayal, about 30 miles southeast of Lahore. "Even if the school

is free, the books are not. And the paper."

Shaffi, whose younger son was playing nearby stark naked, did not even mention

the cost of school clothes. As he spoke, a herd of cows ambled by his naked

child, who scratched at the muddy earth with a sharp stick. Another son,

13-year-old Maratab Ali Shaffi, wore a filthy, torn pair of shorts as he

helped his mother and father pack mud upon a brick wall to increase its

height.

The farmer said it was too early to make a decision about letting the boy go

and join a jihad. But with the drumbeat of resurgent Islam in the air and

hopes of a good job slim for an illiterate youth from the countryside, jihad

is not an unlikely choice.

The family has two acres of land, on which six-inch-tall rice plants waved

above the flooded paddies. They have electricity but can afford only two

lightbulbs. They have no radio or television. No one in the family can read or

write. The local madrasah, by contrast, will provide Maratab a free daily meal

and sometimes a free shirt.

In Lahore, Qadri said he is proud that his school is able to direct youths

like Maratab into holy war in places like Chechnya and Kashmir. But it is

America that seems to be his ultimate target, one he hopes to defeat through

converting its people to Islam.

"There are now over 3,000 mosques and madrasahs in America, and they are

a divine gift for Americans. American civilization is a Monica Lewinsky

civilization," he said with a hearty laugh. "It is empty and hollow

from inside. Islam is the only cultural system that could bear the load of

life for the times to come."

He was similarly dismissive of Hinduism, the religion of about 900 million

people in neighboring India, describing it as nothing more than a system

"of fashions and traditions."

Roots of Anti-U.S. Feeling

Qadri said he would defy attempts by Pakistan's military government to

regulate the madrasahs, beginning with a requirement that they report on the

numbers and names of students and teachers, types of facilities, educational

programs, and financial details.

The government, stung by charges from U.S. officials that it allows Islamic

terrorism to breed under the guise of religious education, has also called for

the schools to begin offering practical subjects such as math and science as

well as memorization of the Qur'an. In addition, the government is asking the

schools to report to local police the names of any foreign students and to

list any religious rulings (fatwas) they issue.

"We believe our rules are perfect, and we will not allow any ruler,

military, or so-called elected representatives to change them," Qadri

said. The News, an English-language national newspaper, quoted several

madrasah heads claiming the data were being collected on the instructions of

anti-Islamic Western forces, particularly the United States and Israel. While

such claims seem far-fetched to better-educated Pakistanis, they are widely

believed by others. Many Pakistanis already feel abandoned by the West since

U.S.-backed rebels expelled the Soviet forces from Afghanistan in 1989,

leaving their country to cope with a huge refugee problem.

Pakistanis also feel it is unfair to blame them for supporting terrorism when

veterans of the conflict in Afghanistan turn to jihad in Kashmir or Chechnya.

Americans are particularly angry with Pakistan for helping the Taliban gain

power in Afghanistan in 1995. Islamabad's military helped organize a guerrilla

force from the Islamic students in Pakistani madrasahs. They were at first

well received in Afghanistan, because they offered hope of ending the five

years of bloody warlordism that had followed the Soviet withdrawal in 1990.

But once the Taliban secured control over 90 percent of Afghanistan, it

imposed draconian Islamic rule--preventing women from working, ordering all

men to wear beards and turbans, banning music and television, and imposing

harsh punishments such as amputation and stoning for theft or adultery.

The Taliban also allowed accused Saudi terrorist Osama bin Laden to remain in

Afghanistan despite a U.S. and UN demand for him to stand trial on charges of

bombing two U.S. embassies in East Africa in 1998, as well as other

anti-American attacks.

Pakistani diplomats say they cannot control the Taliban even if Pakistan is

the only country that recognizes the Kabul regime. The United States keeps

asking Pakistan to pressure the Afghans to hand over bin Laden, and the

Pakistanis say they are unable to do so.

As Pakistan, once a staunch U.S. Cold War ally against the Soviet Union,

slides into Islamist extremism, continued military control, and economic

chaos, its rival to the east, India, has become America's good friend. India's

half-century of democracy has long been admired in America and, since 1990, it

has abandoned its socialist central planning and anti-Western rhetoric.

India's software boom, along with the $60 billion a year earned by Indian

Americans in California's Silicon Valley, has pushed Washington closer to New

Delhi--further angering and

isolating Pakistan.

A group of Pakistani journalists recently asked some American journalists why

their country gets such bad press in the United States. But when queried about

Pakistan's Islamic revival, tolerance of extremism, lack of schools for the

poor, military control, and other problems, the Pakistani journalists ruefully

agreed it was all true.

The root of everything, say several analysts, is that the well-educated

leaders of the country have failed to create a system of adequate public

education for Pakistan's 140 million people. Without that, parents

increasingly turn to the madrasahs, where the fiery mix of fundamentalism and

intolerance is creating cannon fodder for future religious wars around the

world.

Ben Barber is State Department correspondent for the Washington Times.

Al Jazeera is not subtle television. Recently, during a lull in its nonstop coverage of the raids on Kabul and the street battles of Bethlehem, the Arabic-language satellite news station showed an odd but telling episode of its documentary program "Biography and Secrets." The show's subject was Ernesto (Che) Guevara. Presenting Che as a romantic, doomed hero, the documentary recounted the Marxist rebel's last stand in the remote mountains of Bolivia, lingering mournfully over the details of his capture and execution. Even Che's corpse received a lot of airtime; Al Jazeera loves grisly footage and is never shy about presenting graphic imagery.

The episode's subject matter was, of course, allegorical. Before bin Laden, there was Guevara. Before Afghanistan, there was Bolivia. As for the show's focus on C.I.A. operatives chasing Guevara into the mountains, this, too, was clearly meant to evoke the contemporary hunt for Osama, the Islamic rebel.

Al Jazeera, which claims a global audience of 35 million Arabic-speaking viewers, may not officially be the Osama bin Laden Channel -- but he is clearly its star, as I learned during an extended viewing of the station's programming in October. The channel's graphics assign him a lead role: there is bin Laden seated on a mat, his submachine gun on his lap; there is bin Laden on horseback in Afghanistan, the brave knight of the Arab world. A huge, glamorous poster of bin Laden's silhouette hangs in the background of the main studio set at Al Jazeera's headquarters in Doha, the capital city of Qatar.

On Al Jazeera (which means "the Peninsula"), the Hollywoodization of news is indulged with an abandon that would make the Fox News Channel blush. The channel's promos are particularly shameless. One clip juxtaposes a scowling George Bush with a poised, almost dreamy bin Laden; between them is an image of the World Trade Center engulfed in flames. Another promo opens with a glittering shot of the Dome of the Rock. What follows is a feverish montage: a crowd of Israeli settlers dance with unfurled flags; an Israeli soldier fires his rifle; a group of Palestinians display Israeli bullet shells; a Palestinian woman wails; a wounded Arab child lies on a bed. In the climactic image, Palestinian boys carry a banner decrying the shame of the Arab world's silence.

Al Jazeera's reporters are similarly adept at riling up the viewer. A fiercely opinionated group, most are either pan-Arabists -- nationalists of a leftist bent committed to the idea of a single nation across the many frontiers of the Arab world -- or Islamists who draw their inspiration from the primacy of the Muslim faith in political life. Since their primary allegiance is to fellow Muslims, not Muslim states, Al Jazeera's reporters and editors have no qualms about challenging the wisdom of today's Arab rulers. Indeed, Al Jazeera has been rebuked by the governments of Libya and Tunisia for giving opposition leaders from those countries significant air time. Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, for their part, have complained about Al Jazeera's extensive reporting on the misery of Iraqis living under sanctions. But the five-year-old station has refused to be reined in. The channel openly scorns the sycophantic tone of the state-run Arab media and the quiescence of the mainstream Arab press, both of which play down controversy and dissent.

Compared with other Arab media outlets, Al Jazeera may be more independent -- but it is also more inflammatory. For the dark side of the pan-Arab worldview is an aggressive mix of anti-Americanism and anti-Zionism, and these hostilities drive the station's coverage, whether it is reporting on the upheaval in the West Bank or on the American raids on Kandahar. Although Al Jazeera has sometimes been hailed in the West for being an autonomous Arabic news outlet, it would be a mistake to call it a fair or responsible one. Day in and day out, Al Jazeera deliberately fans the flames of Muslim [sense of] outrage.

Consider how Al Jazeera covered the second intifada, which erupted in September 2000. The story was a godsend for the station; masked Palestinian boys aiming slingshots and stones at Israeli soldiers made for constantly compelling television. The station's coverage of the crisis barely feigned neutrality. The men and women who reported from Israel and Gaza kept careful count of the "martyrs." The channel's policy was firm: Palestinians who fell to Israeli gunfire were martyrs; Israelis killed by Palestinians were Israelis killed by Palestinians. Al Jazeera's reporters exalted the "children of the stones," giving them the same amount of coverage that MSNBC gave to Monica Lewinsky. The station played and replayed the heart-rending footage of 12-year-old Muhammed al-Durra, who was shot in Gaza and died in his father's arms. The images' ceaseless repetition signaled the arrival of a new, sensational breed of Arab journalism. Even some Palestinians questioned the opportunistic way Al Jazeera handled the tragic incident. But the channel savored the publicity and the controversy all the same.

Since Sept. 11, I discovered, Al Jazeera has become only more incendiary. The channel's seething dispatches from the "streets of Kabul" or the "streets of Baghdad" emphasize anti-American feeling. The channel's numerous call-in shows welcome viewers to express opinions that in the United States would be considered hate speech. And, of course, there is the matter of Al Jazeera's "exclusive" bin Laden videotapes. On Oct. 7, Al Jazeera broadcast a chilling message from bin Laden that Al Qaeda had delivered to its Kabul bureau. Dressed in a camouflage jacket over a traditional thoub, bin Laden spoke in ornate Arabic, claiming that the terror attacks of Sept. 11 should be applauded by Muslims. It was a riveting performance -- one that was repeated on Nov. 3, when another bin Laden speech aired in full on the station. And just over a week ago, Al Jazeera broadcast a third Al Qaeda tape, this one showcasing the military skills of four young men who were said to be bin Laden's own sons.

The problem of Al Jazeera's role in the current crisis is one that the White House has been trying to solve. Indeed, the Bush administration has lately been expressing its desire to win the "war of ideas," to capture the Muslim world's intellectual sympathy and make it see the war against bin Laden as a just cause. There has been talk of showing American-government-sponsored commercials on Al Jazeera. And top American officials have begun appearing on the station's talk shows. But my viewing suggests that it won't be easy to dampen the fiery tone of Al Jazeera. The enmity runs too deep.